The concept of controlling bombardment of enemy targets, using visual reconnaissance from airborne platforms began in the American Civil War, with Thaddeus Lowe and the Union Balloon Corps. It did not come into its own, however until the First World War. It was always a dangerous mission. The effectiveness of of controlling fires from the air made shooting these aircraft down a special priority of the enemy. The first pursuit, or fighter, planes were specifically developed to counter these first Forward Air Controllers. Their use continued in World War Two, not only by the Liaison/Artillery Spotter aircraft of the US Army and Marine Corps (L-4 Piper Cubs and L-5 Stinsons) and the equivalent Fieseler Storches of the Luftwaffe, but also at home, in the submarine spotting (and targeting missions) by similar Piper and Stinson aircraft flown by volunteer civilian pilots of the Civil Air Patrol, providing targeting for the Army Air Force Anti-Submarine Squadrons. These spotting missions continued in the Pacific Theater and later in Korea, where the USAF used the AT-6 Texan (a WW2 training aircraft) and Army L-19 "Bird Dog" replaced the Piper Cubs. Later, the USAF also adopted the Bird Dog, giving it the USAF designation of O-1. The O-1/L-19 aircraft were in combat again more than ten years later with involvement of the United States in the Vietnam conflict.

Improvements in anti-aircraft fire and the non-linear battlefield of Vietnam made the FAC mission more dangerous than the artillery spotters of World War Two. It also became exponentially more complex. The Forward Air Controller, usually operating alone, was required to find enemy targets in conditions where the enemy was not moving in the open, often through thick vegetation, contact Airborne Command and Control Center (a C-130 Hercules controlling all air operations within a given area), determine the air defense threat, contact the fighter/bombers directed to the target on their frequency, determine the proper ordnance mix, best approach to the target, then come in and fire on the target – only with smoke mind you – and move away so that the aircraft he was clearing in hot would not hit him as they released their ordnance. After all of that, he had to return to the target, assess damage, and provide percent hit and effectiveness ratings to the fighter/bomber aircraft. Of course he had to do all of that without getting shot down himself. This second run was more dangerous than the first. When initially spotting a target, the enemy might withhold fire, hoping that they were not seen by the FAC. After the strike came, they weren't hiding any more…and probably not very appreciative of the FAC being there.

To effectively direct the fighter aircraft, the FAC himself needed to be a qualified fighter pilot. This was the only way he could visualize the strike from the perspective of those he was directing and to know what the best ordnance, ingress, and egress routes for the attacking aircraft. This was not enough, however. The FAC might also be called upon to direct artillery fire, just as in the First World War, or even coordinate strikes with what was then the newest weapon system on the battlefield, Army Attack Helicopters. When directing strikes in support of troops on the ground, the FAC also had to be able to talk to those soldiers or marines – which required different frequencies and radios and to have an understanding of ground combat. The most challenging missions were the rescue of downed air crewman (Combat Search and Rescue or CSAR) or to assist in the extraction of special operations forces. Some missions included both, one as part of the other. In these missions, the FAC was trying to maintain contact with the isolated airman or team, keep another eye out for the enemy, direct “SANDY” ground attack aircraft to keep the foe away from the friend, and provide instructions to the rescue helicopters. Flying profiles took on a special twist as the FAC had to maintain visual contact with the friendlies while not giving their position away. The movie “Bat 21” (which refers to the airman being rescued, not the FAC) does not come close to depicting the true complexity of that operation or the sacrifice of the FAC and special operations forces involved in the rescue. (Also, the airplane in the film is a civilian C-337, NOT an O-2A.) I strongly recommend reading the book, The Rescue of Bat 21 by Darrel Whitcomb (a 23d TASS FAC pilot), to get a true feel for the conditions faced in these rescue operations.

USAF Photo

Adding to the interest level in all of these missions was increasing sophistication of the enemy. This included his ability to listen in on radio transmissions and even spoof them. It also included

ever better anti-aircraft capabilities. First in the form of bigger visually-directed guns, then radar directed guns, surface to air missiles, and finally the emerging shoulder fired heat seeking

missiles. It quickly became apparent that, despite the genuine love many pilots had for the venerable Bird Dog, it was both obsolete and not survivable in the late 1960’s war-form. The O-2 Skymaster

was quickly adapted from the civilian Cessna 337 to meet the needs of the FAC while awaiting the purpose-built OV-10. The O-2 offered better survivability in the form of two engines and two

electrical systems. It could carry more radios, more ordnance, and more fuel. It had some drawbacks from the O-1 in terms of visibility, maintenance requirements and ability to operate out of

primitive airstrips, but it was a necessary transition.

USAF Squadrons flying the O-2A over South East Asia included the 19th TASS out of Bien Hoa, RVN; the 20th TASS out of Pleiku, RVN; the 21st TASS out of

Tan Son Nhut and Phu Cat, RVN; and the 22d TASS out of Da Nang, RVN, and the 23d TASS (where my airplane was assigned), based on the Royal Thai Air Force Base at Nakhon Phanom, Thailand.

The OV-10 was a twin turbo-prop aircraft. It had the dual redundancy of the O-2, but with a heavier payload, real weapons capability, real armor protection, better daytime visibility (more on that

later) and the ability to carry two dedicated aircrew, easing the load on the FAC as pilot and controller.

USAF Photo

Early on, the enemy learned that the US military had some serious limitations in night operations. This was particularly true for our use of airpower to find and strike targets. It was not a new

limitation. The Germans took advantage of it in World War Two but it took on new meaning in the triple canopy rainforest environment. Necessity is the mother of invention and the FACs developed means

to find, target, and direct strikes on enemy forces moving along the Ho Chi Minh Trail under cover of darkness.

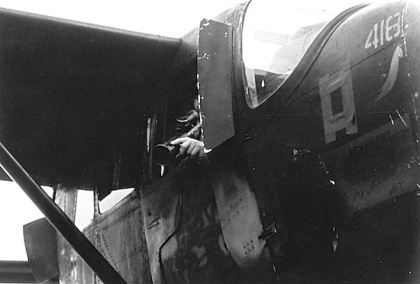

The O-2 has a side window that can be opened in flight at speeds up to 122 knots indicated airspeed (or about 135 knots true airspeed at typical operating altitudes.) This open window could be taken advantage of by a second aircrewman on the FAC team, a Forward Area Navigator, or FAN. The FAN used a “starlight scope” designed to be fitted to U.S. Army infantry rifles. The technique was to use it as though it were a telescope, looking out through the open window. (Night vision devices do not work through a closed window.) The FAC would then drop a flare on or over the target spotted by the FAN and call in the strike aircraft as in a daytime mission. The early OV-10’s were not designed for such night operations. This meant that many of the Tactical Air Support Squadrons could not retire their O-2’s when they got the OV-10s. The O-2s remained in service for night operations.

Photo provided by Col. Jimmie Butler, USAF (Ret.)

The FAC mission continues today, performed by OA-10 aircraft: the Thunderbolt II, or “Warthog” adapted for the FAC and CSAR Mission with specially trained aircrew. All of the OA-10 pilots I have met are enthusiastic about their planes and their mission. Although the USAF higher ups keep wanting to kill the A-10, as a retired Army officer, I cannot think of a worse decision if our goal is to control the battlefield on the ground and keep our soldiers and airmen alive.

OA-10 of the 23d TASS in 2006: USAF Photo